Such a social and relational capital can be the driver for the creation of organisational wisdom . Organisations have long focused on the skill base and on the accumulation of internal know-hows, improving and encouraging people to increase their knowledge base, as if by increasing the individuals knowledge could spontaneously have a massive impact on the whole organisation. An increase in the know-how is essential for an organisation, however, for such a know-how to become an organisational asset, rather than to remain an individual (human resource related) skill, more efforts are needed.

If the relational capital is not adequate and constructive, knowledge of an individual remains an individual personal asset rather than becoming part of a collective and organisational environment.

To capitalise on the learning practices that have pervaded organisations in the past decade, knowledge needs to be put into action. Know-hows need to turn into know-whys.

The urge for innovation calls for new actions and organisations’ slowness in acknowledging that their value lies in the relationships they create within the people and in their ability to exploit the individual skills and knowledge to turn them into a shared value, is one of the key elements today. Diversity and multiplicity of views is essential to move towards innovation (Hays 2008 :11), but organisations need to capitalise on those diverse views. The knowledge accumulated by organisations through information, data, learning incentives are essential, however, they might not be enough if organisations aim to achieve an organisational wisdom.

Knowledge does not lead straight forward to wisdom and perhaps, before talking about organisational wisdom, it’s useful to explain what wisdom is.

To put it simply, wisdom is doing the right thing.

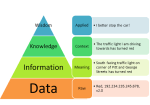

But that’s not enough and I have started looking for more information about wisdom in organisational context, entering the realm of information management… And here I have found that wisdom is said to be the selection of appropriate knowledge for a specific task (Steyn). It is part of the so called DIKW pyramidal model, which, although being criticised, is still one of those starting points worth to be looked at.

DIKW stays for Data, Information, Knowledge and Wisdom, which sees data as the basic constitutive elements of information: to become information, data need to be processed; processed and interpreted information lead to knowledge. As Steyn writes: “wisdom is knowledge, which in turn is information, which in turn is data, but, for example, knowledge is not necessarily wisdom. So wisdom is a subset of knowledge, which is a subset of information, which is a subset of data.” Wisdom is at the very end of such a process and in information management the issue of where does wisdom come from, has involved many researchers in the pars 30 years. Since the mid ‘80s many researchers have provided a hypothetical model to prove the relationship between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom.

Pretty interesting, research in information systems and information management might have been inspired by a poem written by T. S. Eliot, called The chorus of the rock and published in 1934, as Weinberger and others have suggested:

Where is the Life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

Regardless the truth of T. S. Eliot’s influence, they way he puts the question, lead to much reflection.

M. Zeleny is one of the researchers who is credited as one of the first authors to present a DIKW pyramid model which was formally designed in 1988 by R. Ackoff. However, what Zeleny actually proposed one year earlier, in 1987, is the following model, which, considering the same elements, data, information, knowledge and wisdom, translated them in a much organisation-friendly metaphor-based climax: know-nothing, know-what, know-how, and know-why [1]. To manage wisely, as Zeleny says (1987 :60), means knowing why to do something, to manage effectively means knowing what to do and to manage efficiently implies knowing how to do things.

The following schema is taken directly from Zeleny’s cited article and shows how he proceeded in a metaphorical way from the DIKW model to his own model.

If wisdom comes from knowledge, it is however not a sum of knowledge: adding knowledge to knowledge, processing information, does not make wisdom.

If processed data becomes information, processing information leads to knowledge, we need to process knowledge, according to such a model, to get to wisdom. As Hays (2008: 13) says “knowledge does not directly lead to wise thoughts or effective actions and strategies” but wisdom is knowledge put into action and Hays points out that such an action involves reflection. When we consider an organisational context, reflection is a collective activity where individual experiences, learnt skills, knowledges are shared. As Hays (2008) says “reflection is the active and on-going practice of thinking on material, problems, situations, and experiences and their meaning and relation to self”.

While data and information are components and can be generated per se by machines (Zeleny 1987 : 60), wisdom is a purely human capability (Bellinger & Al. 2004, Zeleny 1987) as it emerges from a set of very peculiar elements which can not be replicated by a machine: wisdom and knowledge in fact are relations and therefore can not be made by machines (Zeleny 1987 :60), which can instead generate data and information, yet they are not able to capitalise adding the creative, ethics and social aspects required by wisdom. As Seligman and Steen (2005 :412) point out, the strengths of wisdom consist in creativity, curiosity, open mindedness, perspective and learning. Wisdom is therefore a typically human characteristic, requiring the production of new thoughts and solutions, interests in various fields, mastering new skills and provide insights and suggestions that can make sense to self and others.

But how can this be achieved in organisation?

Hayes (2008 :12) suggests reflection as a mean to put knowledge in discussion and in action. The know-what and the know-how need to be put into action through reflection in order to define a clear and shared know-why, to say it with Zeleny.

In an organisational contexts, as Hays suggests, such a reflection should be performed not in time of need and when things are happening, but when times allow people to meet, join and share their knowledge, reflecting on their skills, needs, visions with no pressures.

If such reflection is the action that triggers the move from knowledge to wisdom in organisation, some sound practices need to be put into place in order to enhance the process and to develop, on the top of the social and relational capital, the sharing of knowledge and the creation of an organisational wisdom.

Collective activities that allow knowledge to be put into action, presented, discussed and shared in a non threatening environment where all participants are entitled to discuss with no external pressures, either related to the role, status or contingent situations which might require immediate and urgent actions, represent the passage from Zeleny’s know-how and know-what to know-why.

Reflection needs that all reflectors put themselves in the picture, taking part actively and participating, interacting, sharing and contributing to the given context (Hays 2008 :15). Reflection requires an action, a collective activity where knowledge is challenged, shared, discussed to move forward, to build and reach wisedom.

Through the knowledge put in action through reflection, a group can turn into a team and define their know-whys.

And the motivation and the strength of a team, lies in their know-whys, where the skills and knowledge (know-what) are shared together with the visions and experiences. And it’s that know-why that can act as a glue that can capitalise on the social and relational capital of an organisation and represent the wisdom, which is a collective good that can enhance a collaborative and harmonised action of a team. Is that know-why that creates the synergies that Hays (2008) sees as a missing point in today’s organisations: the lack of those synergies is one of the causes that prevents organisations to move from the knowledge to the next level, where knowledge in action through sharing, negotiation and agreement can lead to organisational wisdom.

There might be many techniques to achieve organisational wisdom, but when it comes to sharing knowledge and experiences, to negotiation of knowledge and literally to put knowledge into action, LSP again proves to be a solution for a current and rather urgent need of todays’ organisations.

By constructing and reflecting with the mediation of LEGO bricks, organisations have the chance to move one step further and capitalise efficiently on their social and relational capital, mapping the know-hows and know-whats and put knowledge into a real action through the hands’ driven reflection, which can lead and build, not only a shared model, but what has been overlooked for too long: organisational wisdom. And in times where innovation is considered as the ultimate solution to survive the tough times, the whys – the know-whys – become pivotal: it’s not about knowing how to do things or what to do, it’s all about knowing why should we do things.

Note: much discussion still goes on about the differences between know-how and know-what. This article takes Zeleny’s model as it is and applies it, with no discussion about the meaning and implications of know-hows vs know-whys.

References

Ackoff, R. L., (1989) From Data to Wisdom. In: Journal of Applies Systems Analysis, Volume 16, pp 3-9.

Bellinger, G., Castro, D., Mills, A., (2004) Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom. In: System-thinking.

Hays, J. M. (2008) Dynamics of organisational Wisdom. In: Working Paper Series. Vol. 3, Issue 3.

Seligman, M., & Steen, T. (2005), Positive Psychology Progress, American Psychologist, Vol 60, n. 5 July-August pp.410-421

Steyn, J. http://www.steyn.pro/km/definition.html

Zeleny, M. (1987) Management Support Systems: Towards Integrated Knowledge Management. In: Human Systems Management, 7-1, pp. 59-70.

David Weinberger, (2010) The Problem with the Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom Hierarchy In: Harvard Business review

![Zeleny's model [1987]](https://legoviews.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/zeleny1987.jpg?w=716&h=226)